In this project, I examine how novel character representations emerge in global narrative systems. Characters, after all, are among the most diverse today as they have ever been, and their representation is essential to understanding the underlying implications of narrative systems on global scales. In the past decade alone, they have been represented by beams of light, rivers, statues that only move when they aren’t being observed, talking ants, paper airplanes, sea sponges, talking toasters, and nuns who sing and dance in unison. Users (readers, viewers, consumers) of narrative experiences now have access – because of two centuries of unimaginable growth in communication technologies – to narratives from, by, and about people whose actions, belief systems, and own identities force us all to reflect, question, and imagine. We’d all hope this brave new world, which was not long ago a brave new horizon, has done more good than harm to our ways of life. Yes, we have access to more information than we ever have before. People still try to control what we can and can’t see, and those subversive narrative consumers among us still sometimes ask the question: what aren’t I seeing? Yet we continue to move forward, each year understanding a little bit more of the stories behind the experiences of others, reflecting more deeply, and taking actions to adapt to a world of so many voices and interfaces. Our world has so many stories that one would be forgiven for opting to not consume the same story twice. Such is the great charade, or the great tragedy, of our networked world: while we can access more stories from more places, we are liable to think that once we’ve heard a story, we’ve heard it as it was really intended. In her The Dangers of a Single Story, novelist Chimamanda Adichie reflects deeply on the ways that prejudice and fear can be stoked by the fires of misinformation, which today travel more quickly than they ever have. One would be forgiven for thinking that the way a story is packaged reflects the story itself—where it came from, or whom it came from, and through whose many hands the story has been modified ever since.

But through complexity comes simplicity. The complication of the narrative ecosystem has created, surprisingly, some of the most simplistic narrative forms to emerge on a global scale in centuries, yet whose exact technical mechanisms are some of the most complex in our history. Who wants to travel to experience a story when we can experience it right here, wherever we happen to be? Who wants to pay more money for an experience that requires more physical and emotional commitment on our part? Shouldn’t we be paying more to do less?

Botanical Beasts

Monsters, or Beasts, are chimeric in nature; they possess the combined features of several animals. Many of the greatest and most despicable monsters (historically) appear to possess uniquely human characteristics, physiological or otherwise. Monsters designed for modern audiences possess characteristics of humans, animals, and plants. The clearest example of this comes to us from the 1978 Dungeons & Dragons: the Demogorgon.

The beast—inspired by the Pagan demon of the same name—became among the first fantasy beasts born into the 21st Century. The Demogorgon was depicted as bipedal with two baboon heads, tentacles for arms, a scaled torso, and birds’ feet. Standing like a man (or like Beowulf’s Grendel) yet behaving like an intelligent beast, it would later become the most iconic of 21st century’s depictions of man-made monsters, made so with the 2017 release of Netflix’s Stranger Things, a streaming web series about a group of D&D-playing kids who have accidentally stumbled upon a gateway to the “Upside-Down,” which for our purposes we can liken to D&D’s “Veil of Shadows,” of which the historical Demogorgon is the prince. What’s most interesting about our fascination with the Demogorgon today is not its overnight celebrity, but its botanical design features—making it as much plant as animal.

Flash forward to 2017, the year that the rest of the world came to meet the Demogorgon. This time around, however, the beast was noticeably different than in its previous iterations. For one thing, it was as much plant as it was animal; for another, one of its most essential features was removed—its two sets of eyes. Like many other modern monsters, the Demogorgon appears to “see” using a sort of sixth sense, at the same time seemingly wired into a hive mind of other Demogorgons, like ants or bees in a hive.

However, the Demogorgon is not the only botanical beast drawn from mythic, fantastic, or fictional narratives. Immediately, we see that characters of this sort are not only common, but popular with vastly different demographics and age groups.

Pa'u Zotoh Zhaan

Farscape

Zhaan is quite literally a plant born of a race of aliens who, like plants on earth, source much of their energy from stars like our Sun. Like Groot and others mentioned here, Zhaan is gifted with healing abilities beyond human comprehension or the efficiency of known medical remedies (like them, Zhann's abilities derive from Nature itself). The ability of plants to not only heal themselves but "regrow" and come back from what humans perceive as death is unbelievable. Plants propogate and manifest in far more variants than do animals, although as seen in fungal systems, there was a time at which biological trees were united across known organic classifications. .

Groot

Guardians of the Galaxy

Talking Trees, or "Sapient Trees," are common in mythology, representing ultimate, transcendent wisdom. Like the Ent from "Lord of the Rings," which comes from the Latin "ent" meaning "a giant," Groot is a sapient tree born from another world. It is curious that so many of our animal companions serve to connect us with the natural world, but perhaps obvious when considering the role of stories to frame us, and characters like us, within established natural environments and settings -- which in the history of our species have certainly far exceeded those that have been developed by human hands.

Watermelon Steven

Steven Universe

In "Steven Universe," the aptly named hero (Steven) inherits the ability to heal organic matter through his bodily secretions. He can re-grow flower fields by kissing them, and even bring people and animals back to life by crying on them. Somewhere between human and god(dess), and with a magical and alien "Crystal Gem" for a mother, Steven has many curious healing powers, including the ability to give sentience to newly sprouted fruit. Through this power, Steven creates a society of watermelon Stevens, who quickly develop unique languages, practices, and identities.

DEMOGORGON

Dungeons and Dragons

Like many plants, Demogorgons reproduce asexually, producing spores that enter host bodies through inhalation or ingestion. Like seeds, these spores travel with their hosts until a more suitable environment is found—usually a body of water, which is particularly well-suited to the Demogorgon’s earliest development stages. The modern Demogorgon’s head, rather then being that of a dual-minded primate, is instead modeled after a carnivorous plant, consisting of five teethed pedals that clamp down on prey before thick salivary glands and rows of jagged teeth, like those that might be found inside of a Venus Flytrap.

Trowbridge R (May 2011). "Waiting for Sophia: 30 years of Conceptualizing Wisdom in Empirical Psychology". Research in Human Development. 8: 111–117.

The Demogorgon's original manifestation. Wizards of the Coast. Dungeons & Dragons.

Graduate Thesis Project Daniel T. Kessler

NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study Updated 12.12.19

Graduate Thesis Project Daniel T. Kessler

NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study Updated 12.12.19

You may use this feature to take and submit notes.

Agency

Avatar

Conflict

Character

Frame Theory

Intelligent Systems

Future Narratives

Narrative Discourse

Storyplaying

Virtual World

You may use this feature to look up commonly used terms or to recommend useful additions.

Fungal Friends

Anthony Rapp as Lt. Paul Stamets from Star Trek Discovery (CBS). Rapp’s character, named after the eminent mycologist, has been mysteriously fused with an interdimensional fungal network that allows him to “fast travel” or “teleport” between space, time, or both. In this story, Stamets is central to his crew’s ability to discover and interact with new worlds, and essential to the show’s overall plot progression. Long story made short, Stamets exists between the interconnected galaxy and the human realm, a status now shared by us, the User. Like other characters who are part human, part plant (I say plant because of the way that they use fungal networks to communicate across long distances), Stamets can communicate in ways that could never have existed just a decade earlier. Most especially, it is this embedded, networked character who represents the possibilities and dangers of a networked society.

Tardigrade

Star Trek Discovery

Star Trek Discovery's tardigrade - or what would be a very alien species of tardigrade able to materialize and dematerialize at will, is able to communicate through Lt. Stamets, joy, fear, pain, and other emotions. In our universe, tardigrades (or "water bears") exist almost everywhere, from the frigid Arctic to the heat of the intense, near-molten Mariana trench. Tardigrades exist somewhere between humans and fungi, and indeed exist almost everywhere that fungi do. Like many microorganisms, tardigrades use mitochordial networks to travel and communicate.

Lt. Stamets

Star Trek Discovery

When the crew gets stuck in an alternate (dystopian) dimension and meet their “evil twins,” so to speak, the crew must come to terms with a shifting sense of identity and self. As Gauffman might say, their roles shift to accommodate their new realities, and slowly the crew turns toward one another. Eventually, Stamets is able to transport the crew back to their original dimension (or so we believe), which, it turns out, is decomposing alongside every other dimension. Stamets discovers that the fungal network of which he is a part is being destroyed by a unique power source found on the crew’s evil companion ship. This source is corrupting all matter in the universe and across all dimensions.

Animal Familiars

Familiars exist throughout mythological sources and into the modern day, but we rarely view their contemporary manifestations in the same light--as spiritual guides and other-worldly beings. The houses from the popular "Game of Thrones" franchise (of books, novels, games, etc.) are frequently aligned with animal spirits and have other-worldly powers as a result. Most notable are the Targaryan and Stark houses, who respectively align themselves with dragons and dire wolves, or elementally with fire and ice.

We see here the continued tradition of elemental alignments of non-human and even human characters in mythological and epic stories. Before industrialization and the mass-proliferation of animal novelty items, toys, and objects, it is likely that the most common representation of animal familiars was in global coat-of-arms practices.

Many more of today's most popular video game, movie, and book characters play the role of the animal familiar, and many of these exist as faraway ancestors of ancient mythological characters. Here, I examine some of today's most iconic animal companions, or "familiars," and observe the origins of their characters.

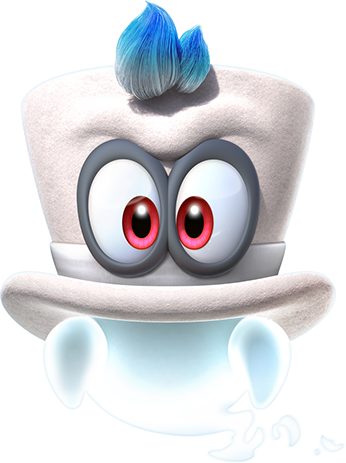

Cappy

Super Mario Bros.

Cappy is neither a hat nor a ghost, but a shape-shifting being who inhabits one of the many worlds visited by Mario throughout his adventures. Cappy, seeking to protect his family, "posesses" Mario's hat and thereafter accompanies him on his journeys. There is no clear reference point for Cappy's origin outside of the Mario universe, although spirits and ghosts are often afforded the role of side-kick, such as if the case in many ancient and contemporary stories.

ROACH

The Witcher Series

Roach is to Geralt of Rivia (the hero of "The Witcher" book and video game franchise--and soon to be Netflix show) as Rocinante is to Don Quixote. There are many other mythic and "heroic" horses in worldwide narrative tellings, going back to the earliest Norse mythologies (in which, for one, Loki turns himself into a beautiful mare and is impregnated, giving birth to a six-legged horse--Sleipnir--that is gifted to Odin).

PIKACHU

Pokemon

Before being played by Ryan Reynolds in an animated-live-action film, Pikachu was designed, back in 1996, to be the Pokemon franchise's leading character as he was approachable (a variant on the house mouse) and his circular features and familiar appearance made him attractive to children. Pikachu can be seen as belonging to a long line of mythic mice and rodent-like creatures, most notably the Japanese Raijū ("ra-ee-chu"), a celestial lighting spirit that took the form of mice, rodents, foxes, and cats. Pikachu's "final form", in the Pokemon world, is likewise named "Raichu."

Palico

Monster Hunter World

Palico was created for digital interaction, for video game purposes, and later transferred to comic strips, fan fiction, and other more diffuse narrative forms, including gifs and memes. Cats are common familiars in druidic, shamanic, and wiccan practices globally. In its home of "Monster Hunter World" more specifically, however, it is further notable that the Palico appears to be a native species on a planet inhabited, otherwise, only by terrible, Jurassic beasts. The Palico also refer to humans comically as their "meowsters," although perhaps this reference is darker than its manifestation would entail.

Bird companions hold particular meaning cross-culturally, representing a "third eye" and external source of wisdom. The wisest of the ancient Egyptian gods, Horace, had the head of a falcoln and was half-man--both between the human and godly worlds and surpassing them both.

Muninn

Norse Mythology

In Norse mythology, Muinn is Odin's faithful raven companion, representing Odin's mastery over memory. The raven has since been associated with wisdom, although this association may have more to do with a raven's innate intelligence than with its narrative associations. Nonetheless, the raven, as being a "third eye" that can see either the past or future, is now represented in contemporary narratives like Game of Thrones, in which we see many examples of raven companions, most notably Lord Commander Mormont's pet raven, who appears to take a liking to whomever currently holds Castle Black.

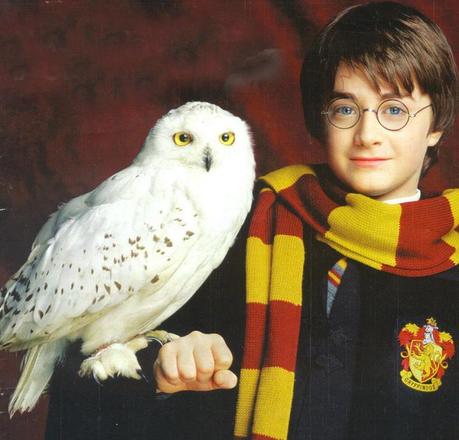

Hedwig

Harry Potter

Hedwig is introduced in the first Harry Potter novel and quickly becomes a key support character in the story, delivering vital messages and being, generally, a constant companion to the story's protagonist. Like ravens and other highly intelligent and distinctive birds, owls have been favored in narrative systems for thousands of years. Perhaps due to their similarly round features, owls are also key characters in many of the globe's most popular folklores, fairy tales, and children's literature.

Mechanical Monsters

With the age of artificial intelligence comes robotic heroes who couldn’t have existed prior to the industrial revolution. As we gain a deeper understanding of psychology, physiology, we also begin to use character development as an opportunity to practice what we’ve learned. When we depict androids or artificially intelligent machines in modern narratives, we often encounter characters who lack eyes, ears, hands, or other such sensory features—accounting for machines’ extrasensory nature. A particularly problematic example is that of "Nier: Automata," a transnarrative (manga, video games, films, etc.) focusing on highly sexualized humanoid android characters who, you’ve guessed it, have no eyes. Another issue worth raising here is that gender, in robotic characters, serves no obvious purpose beyond the strictly narrative. But perhaps this "genderizing" has gained a new purpose, one that requires us to view the situation from the perspective of the gendered robotic character--to assert for him a true, humanistic individuation. Thereby, and by masking the individual intelligence within a social system, the robotic character becomes as any other human character, but with the extended intelligence and capabilities of an optimized, mechanical system.

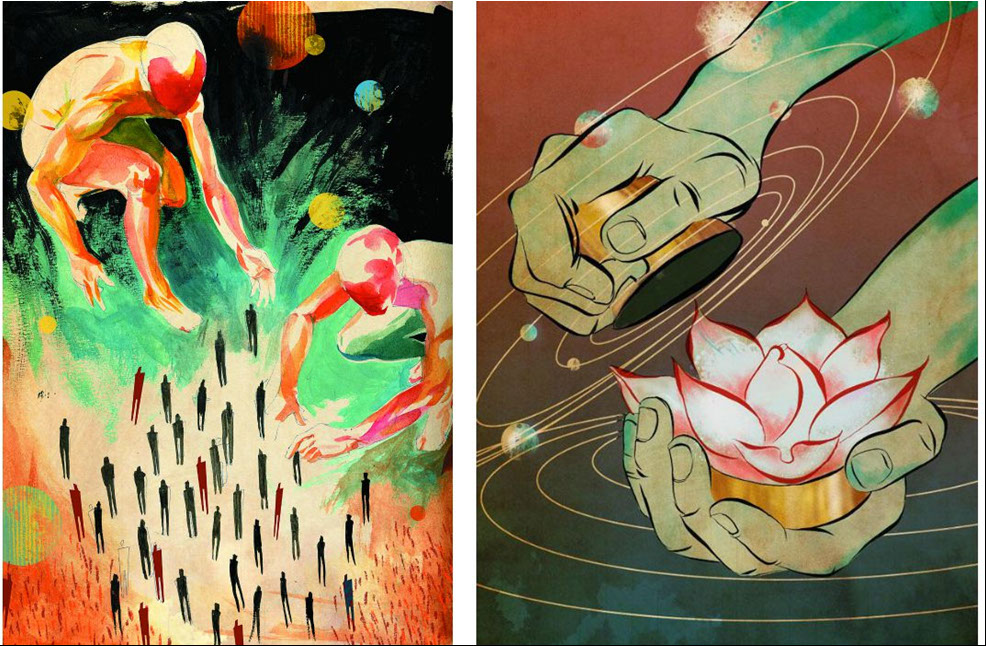

World Mythology Depictions. Figure 9, Juok the Creator molds Egyptians from clay and Southern Sudanese from black earth. Noah MacMillan. Figure 10, The lotus blossom that births all creation, awakening from the hands of Lord Vishnu, immersed in the stars and heavens. Noah MacMillan

Mythic Heroes

Mythic heroes lay somewhere between human and god, with their supernatural powers bestowed upon them by spiritual or dietic forces. But should a superhuman (not necessarily a “hero”) arise by “natural forces” or by virtue of themselves, they are eventually destroyed by the jealousy of these same Gods. A prime example is the Greek myth of Arachne the Weaver – in which a mortal weaver defeats Athena in a contest of artistic prowess, only to be turned into the world’s first spider, forced to weave for the rest of her days as a monster. Another example is the story of Cupid and Psyche—in which a mortal woman, Psyche, is born with such beauty that the god Cupid falls in love with her (although this tale has a much happier ending than that of Arachne).

But today’s heroes weren’t chosen by Gods, but by Darwinism. They were created by natural (albeit imaginative) scientific developments (Captain America, Iron Man) and mishap (Spiderman, The Hulk, or Star Trek Discovery’s Lt. Paul Stamets), or else they were the natural result of evolutionary mutations (Wolverine is a combination of several of these hero types).

Mythical heroes from around the world share key characteristics, from which we can often trace the lineage of the modern hero. These heroes were, for the most part, incredibly strong, a characteristic almost not worth noting, since the hero is known so commonly to use his strength to solve even the most complex of problems, making him something beyond human. The hero also possesses characteristics of the devil—a cunning, tricky intelligence that allows him to outsmart even gods and demons at their own games. This, too, has not changed. The hero has a sort of vision, a sort of closeness to the darkness, that puts him on the edge of evil—a distance he must nurture, for he is unable to succeed in conquering the dark without it.

Mythic heroes have barely gone out of fashion, becoming today's super heroes and leading protagonists. But some things have changed about how heroes are made. Instead of achieving victory, or triumph, by innate action alone--by "being who they were born to be" and using their innate super-human abilities--today's heroes are more easily identified by their penchant for existential self-reflections, self-sacrificial behaviors, and knowledge-seeking activities that are perhaps only possible in for heroes portrayed from within a scientific era, although we could argue this point for some time. Such moments as Senua's revelation of strength in the role-playing game "Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice" are ideal examples of this practice. Within a moment, after the heroin receives her holy blade, and after which the user engages in extremely difficult simulated combat, a heart-wrenching and terrifying cut scene in which Senua (the user) manifestly pulls her dead fiance's soul (from the Nordic Hel) and-- through sheer will and concentration-- forces him out of her mind. This significance is easy to overlook for those unfamiliar with schizophrenic experiences, but nut so when users experience this story for themselves and in the first-person. A breaking of a tragic cycle is no easy feat in narrative systems, and when one is portrayed with fearlessness, it can be particularly rewarding for users of these systems.

Folk Heroes

A small distinction should be made between mythic and folk heroes, with folk heroes being those belonging to a narrow and typically far more specialized geographic region. Many folk heroes appear at first to be modifications on larger mythic heroes, whose adventures tend to be more numerous, violent, and political. American folk heroes are easy to spot, from the ballads of John Henry to the tales of Johnny Appleseed. Japan is particularly well-known for its multitude of folk heroes. One of the most recognized is the "tale" of Keguyaheim ("child of the bamboo"), the story of a woman from the moon who was left on Earth, as a child, to protect her from a violent political revolution on her home world. The story begins when Keguyaheim is discovered in the bamboo forest of a childless couple. The couple takes the girl in and raises her as their own, and they are blessed thereafter to find gold in every bamboo shoot they cut. They became very rich and when Keguyaheim comes of age, she is presented with three princes, whom--like the Celtic CulHollan and so many Norse hores--she gives impossible tasks to complete in exchange for her hand in marriage. Two of the princes fail, but the third--who was the emperor in disguise--succeeds, and Keguyaheim must tell him the truth: that she is from the Moon, and that she cannot live here with him. She gives the emperor one drop from the Elixer of Life and bids him farewell. He would wait there atop Mount Fuji for the rest of his life, giving it the name "The Mountain of Great Warriors."

What Does a Hero Look Like: Then & Now

In early 2019, while I was just getting into the meat of this thesis, the Internet erupted over a picture of Steven Pruitt. If you aren’t familiar with that name, you’re not alone: Pruitt is responsible for editing nearly 3 million articles on Wikipedia and for writing at least 35,000 more. For context, if you had visited Wikipedia and perused any article this year, there's about a 33% chance that Pruitt had a hand in writing or editing it.

In a society that uses knowledge as both a weapon and a resource, the value of information cannot be overstated. Pruitt's true gift, I believe, was that of narrative access and agency. Those places on Earth without Wikipedia access have far greater issues than those that an encyclopedia may be able to solve. But for those with even the most remote access to the Internet of Things will have lived in a more democratized world as a result.

This brings us back to our original observation. What is it about Pruitt's appearance--rather than his service--got Internet users so activated? At the time of his first public interview, it appeared that half of the Internet wanted Pruitt to be lambasted because, in their opinions, he looks kinda funny. The other half--were we to dilute "the Internet" into a social schism only several hundred thousand miles wide--found Pruitt to be a hero. In a world that privileges access to information, Wikipedia stands as a powerhouse of social justice. Pruitt, a humble writer whose work has absolutely changed the landscape of virtual narrative access for so many people around the world, is exactly the kind of hero we’ve been waiting for. His strength is not measured by the hammers that he can wield, but by the knowledge that he can share.

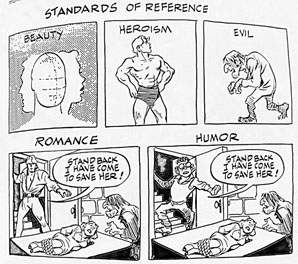

A clipping from Will Eisner's "Graphic Storytelling & Visual Narrative"

A meme about Steven Pruitt that spread quickly in the days following his first public interview.

The Danger of a Single Story

John Duncan’s 1912 depiction of the Fomorians, a race of one-legged, one-armed subhuman giants from Celtic mythology (shown in the above historical depiction as two-legged). In Celtic lore, the Fomorians were believed to be the original settlers of Great Britain. They were also believed to be the first of five cultures that the Celts had to defeat before eventual unification. In thinking of The Danger of a Single Story, I wonder if maybe the Celts – or who would eventually become the Celts that is why the Follorians have one arm and one leg. Maybe that is why monsters are so monstrous. We must villanize the other whom we feel we must eradicate