![Material & Narrative Innovations in material science, including but not limited to those subjects described below, open the doors for artisans and artists to create new and different kinds of narrative experiences. This should come as no surprise, since at the heart of narratives is the practice of making,wherein materials are crafted into things (imbuing them with properties that can be harnessed) by various means and methods. Mathematical principles are universal in these practices, although not always regarded as such. At the heart of making is materials, the physical justification and constitution of all things, actual or conceptual. Materials are so important that international flight regulations prohibit the carry-on of an entire material category--liquids--for which it is notoriously difficult for machines to tell apart the safe and the dangerous (Miodownik, 2003). We digest materials, feel materials, play with them, and so forth. They may even play roles as characters in the stories of our lives that we each produce and replicate. Miodownik, whose Stuff Matters has been a formative resource in my understanding of material applications, has broken down the problems of "making things" into two categories: (1) identifying the right materials for the job (materials define properties, and therefore what one can do with something made) and (2) finding a way to shape these materials into their desired functionalities. Clear and diverse real-world examples exist everywhere, but I choose to use that of performance rituals and behaviors. There is much that separates a film and a stage play. But they are, overall, made of mostly the same stuff. Their materials--down to their use of human bodies both as actors and audiences--appear to be at one time unusual and obvious expressions of narrative systems and activities. Materials, after all, make up everything that moves, acts, shows, or tells. They make up all that is or ever has been, including us. How we live our lives today is largely determined by the materials that make up our surroundings, tools, and interfaces -- and which have made possible technologies that have altered the nature of our global societies. The disposable razor blade, which is made of a specialized flexible metal, was not scientifically possible 200 years ago, and helped define a capitalistic economic scheme whereby products were built for perpetual failure, issuing resulting in perpetual purchases. With the exception of a few heavy metals, none of the elements (which make up materials) that we recognize today had even been known to science at the time that Shakespeare wrote his sonnets. Plastic, among the only materials that can be cast, melted, and recast in ad infinitum, was only discovered in the 1930s--and we have, since then, filled our oceans, class rooms, closets, and super markets with it. Concrete is among the strongest and oldest "made" materials we have, and yet was structurally useless as a foundation until steel rebars were added less than a century ago. Plywood, another recent invention, allowed furniture be built more quickly and effectively, and allowed for wood to be bent in ways that would otherwise be impossible (although a few could be bent with high-power steam or kerf cutting, a technique by which an artisan removes small slips of wood to bend it more easily). Printing We can now print objects and even homes. The scale of this printing is nothing near that of the paper or cloth printing machines of today, but one day, I expect it may exceed our use of paper- and plastic-printed narrative artifacts. 3D printing allows us to print using ceramic, glass, metal, plastics, and rubber. But in medical research, 3D.printing is even being used to "print" stem cells at specific locations in space in order to create artificial human tissue for transplant. Candles Early American sailors probably could not have foreseen that one day, our evening light would be provided by those very same objects that we sought to illuminate, and whose words and characters we wished to interpret and imagine. A cultural shift largely from print narratives and largely toward digital interfaces dramatically alters the materials required for narrative experiences. Miodownik describes our early use of candles, for context, as follows: "[Early American sailors] worked out that the oil you get from a whale has a honey-like consistency, which is very amenable to an oil lamp… It flows really well and has a so-called flash point of 120 degrees"--(the temperature at which it will catch fire)--this is compared to olive oil, whose flash point is 300 degrees. People started killing whales "on an industrial scale," killing over a quarter million whales "so that people can have more evening light, to play cards, read books… because the thirst for evening light was so great." (34:30 in Miodownik's lecture Delightful and Dangerous Liquids). microchips Today, however, our thirst for nighttime narratives, and for immediate and on-demand narratives, has led us to strip the earth of many more of its rare resources, including gold, nickel, copper, crystals, and rare metals. While we once reaped and harvested animal materials, we now abuse human resources worldwide, and endanger human lives, to harvest metals and other materials necessary for contemporary digital applications. Material Creation The materials that are used to generate, replicate, and share narratives can tell us more about the narratives themselves. Narratives that can be replicated digitally in their exactitude—such that we might call digital or quantum files—and these tell us about the states of a narrative. It needn’t be performed live, for example, or shared or retold vocally, although such could certainly be done. The permanence of a bronze sculpture—yet the need to clean it of rust over time—tells us that it is intended to be experienced for at least several generations, if not longer, and thus represents a human quality, or truth, that is assumed to be relatively universal or innocuous—rather than something brief, like a commentary on a local event that holds no historical significance. The weight of such a sculpture, likewise, tells us that it is intended to be placed within a space and not moved. It was designed, after all, with the intention of a particular space in mind, one assumes. Such observations as these hold true over time. But some others require more scrutiny, the kind of which may not be possible in this thesis alone. Paper is intended to last as long as its caretakers allow—with some paper documents lasting thousands of years, and others mere minutes, or until they come into contact with water or open flame. The fortune in a fortune cookie is intended to be read once and discarded, and so is small and concise. The sheep’s leather of an ancient Torah scroll allows it to be longer and more durable than paper codices, with wooden or metal handles for usability, and to reduce the wear on the scroll itself. From this we can extrapolate that if something is made of leather, it is intended to be used for a long time relatively, but relative to what? In this case, the item may be used for thousands of years. And yet a leather wallet is only expected to last for a few years, at most, before wearing down to the point of replacement. What is the difference, then, between a Torah and a wallet, that dictates this difference? One is handled with great care and seldomly, while the other is handled with little care almost every day. This is, immediately, the essential difference between the longevity of these objects. But through what other lenses can we compare artifacts of similar materials and distinct contexts? Books are made of paper, just like Ikea furniture instructions, but one is laminated on the outside to increase its longevity, whereas the other is not. And so we see an immediate difference in the quality and context of these materials. More research is needed to determine how narrative forms, genres, and experiences can be viewed and reconstructed using material science frameworks. My next step in this inquiry is to examine material science classifications and qualities, such as flexibility, crystallization, solidification or liquefaction, as narrative modalities. Such, at least, is a current interest of mine.](images/u11332-50.png?crc=3803791310)

Graduate Thesis Project Daniel T. Kessler

NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study Updated 12.12.19

Graduate Thesis Project Daniel T. Kessler

NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study Updated 12.12.19

You may use this feature to take and submit notes.

Agency

Avatar

Conflict

Character

Frame Theory

Intelligent Systems

Future Narratives

Narrative Discourse

Storyplaying

Virtual World

You may use this feature to look up commonly used terms or to recommend useful additions.

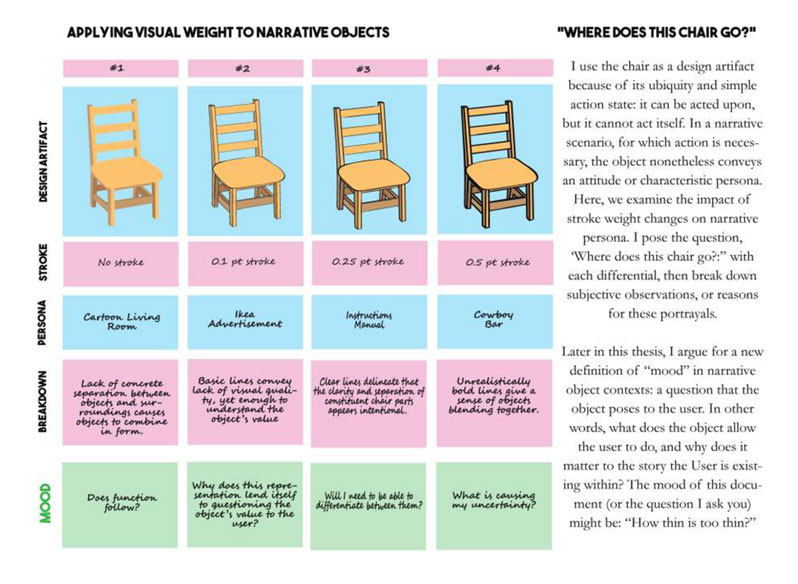

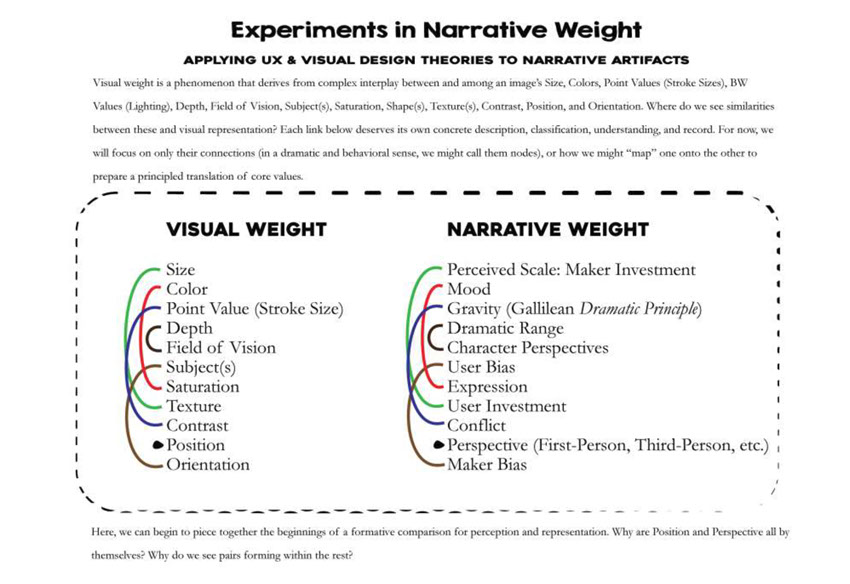

Visual Weight

Narrative Weight

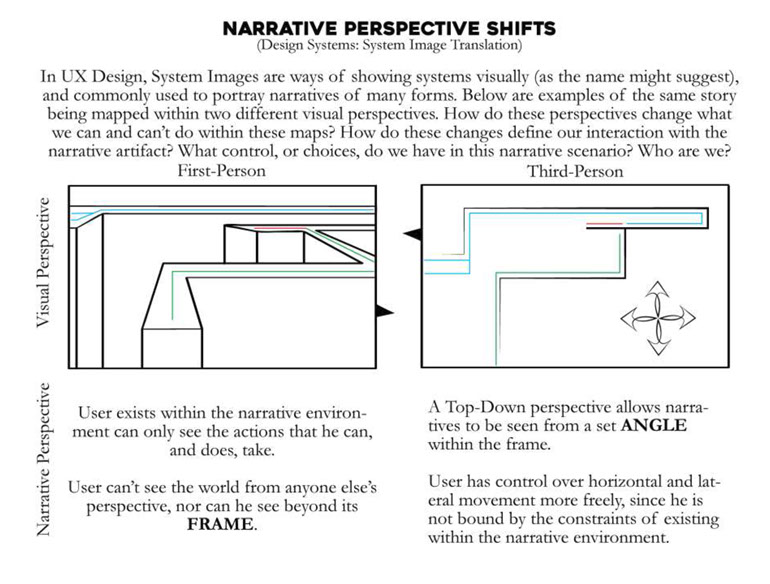

Perspective Shifts

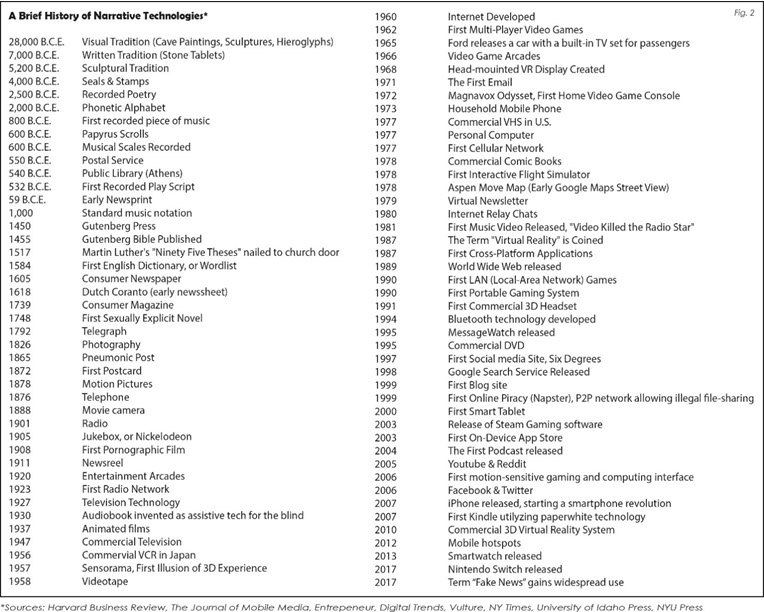

History of Narrative Technologies

Act Structures

In this section, I have redrafted variants of several dramatic structures that are in popular use today. In the future, this section will have more information.

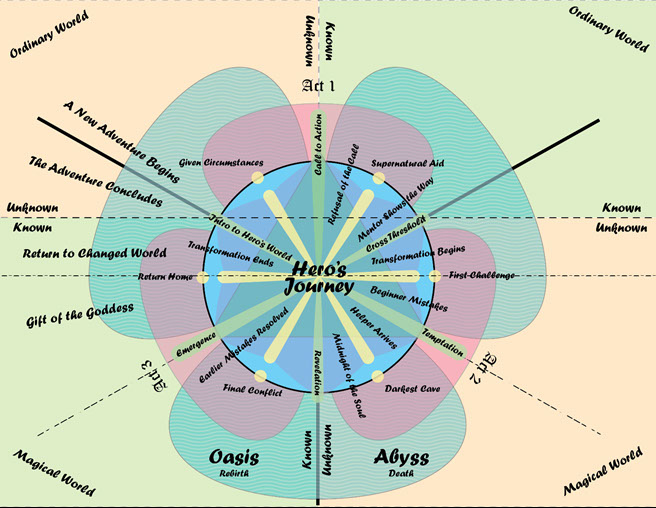

Hero's Journey (Redux)

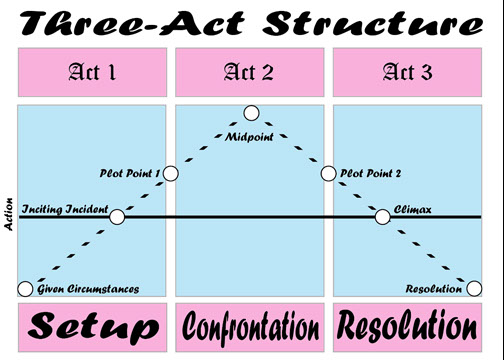

Three-Act Structure

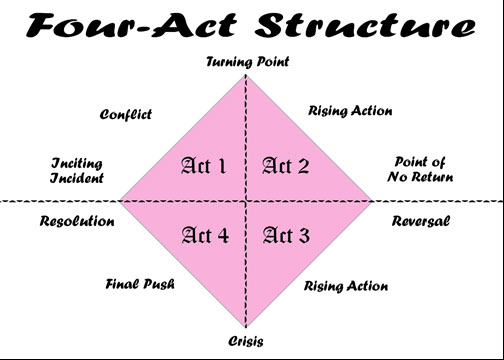

Four-Act Structure

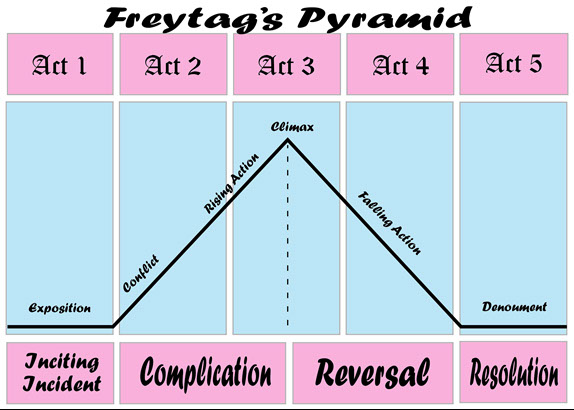

Freytag's Triangle (Five-Act)

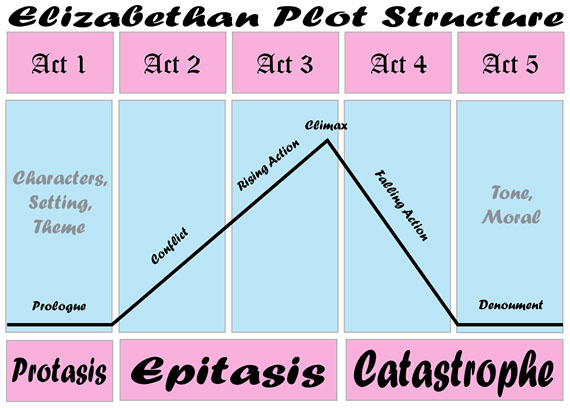

Elizabethan Act Structure

Aristotle portrayed the story as a straight line; Freytag described it as a triangle, with Tension on the X Axis and Time on the Y Axis; Campbell portrayed stories instead as repeating circles, or cycles; and in interactive narratives, the story is shown as a network of interconnected arrows (a directional tree graph), with plot points determined by user input. In examining these and other portrayals of story formats and functions, I argue for the continued universality of a three-act structure—a beginning (rising action), middle (conflict), and end (resolution)—but with the additional dimension of user input.

Return to the Changed World: Once the hero returns to the changed world, he must then come to terms with the ways in which it has changed, which are not always those ways that he had first anticipated or sought out when he had first journeyed from comfort to embark on his heroic adventure. Often, this means that the hero must come to terms with past choices that they never considered to have the impact that they did. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes is ripe with these sorts of occurrences, as are many other mystery or crime dramas today, in which criminals—or those who performed criminal acts, often for reason with which audiences can at least partially empathize—must realize their mistakes in order to accept their guilt and more forward with their own lives.

Narrative visualizations allow us to see a narrative’s structure—its skeleton, composed of bones that each serve a role in the organism itself, performing unique actions that deliver unique results. The skeleton of a story, in a way, is the layout of its mechanical parts, or the parts that move and act. But our understanding of stories today the same as it was when our most popular narrative visualizations first came about? Perhaps the most famous and talked-about structuring of the narrative comes to us from Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Here, I redraft the hero’s journey with several key changes. First, rather than going from known to unknown and then back to known, I show the hero going from the unknown to the known, back to the unknown, to the known, and finally the unknown.

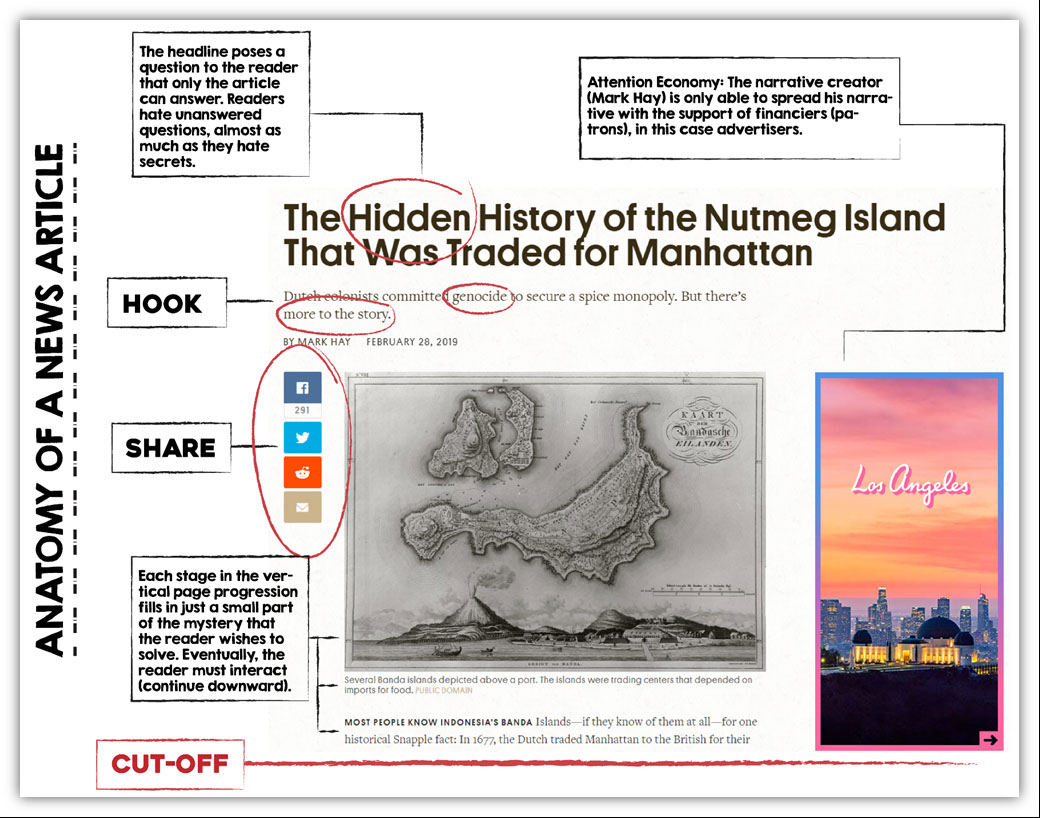

Anatomy of a News Article

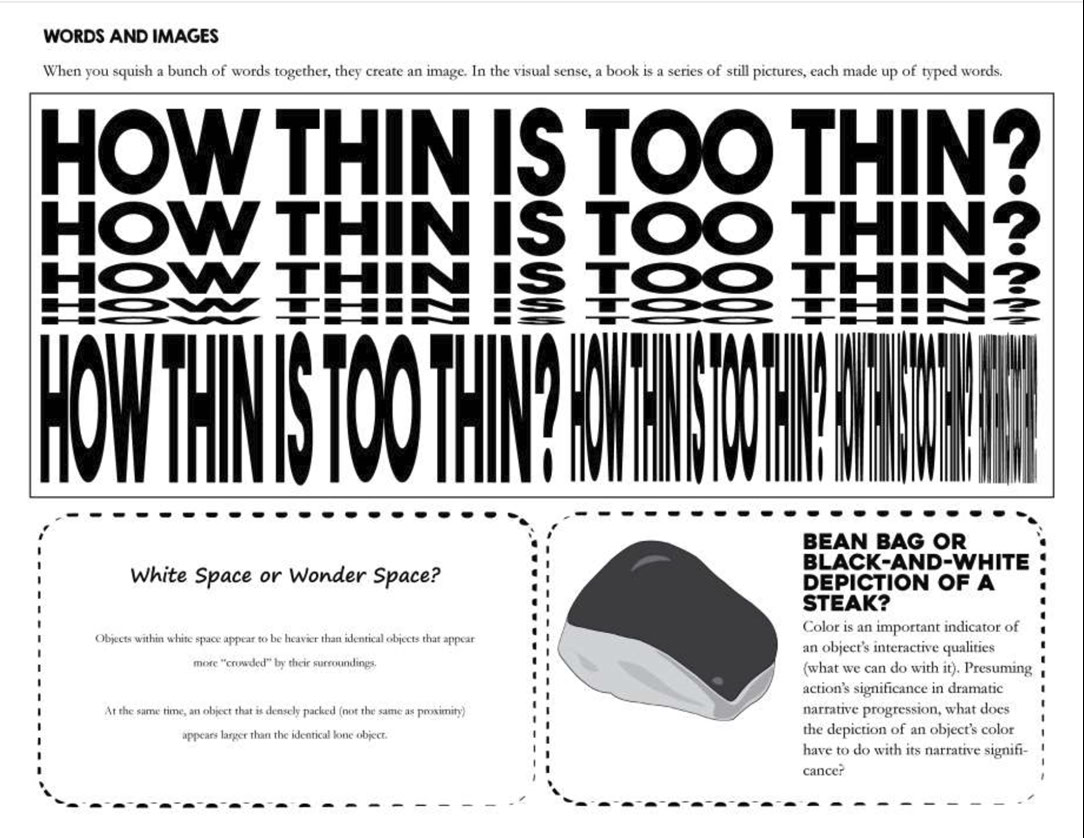

Words & images